Historical Christadelphian Approaches - 5: Difference between revisions

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

===<span id="3"></span>5.3 Other approaches=== | ===<span id="3"></span>5.3 Other approaches=== | ||

It is noted that other approaches, which may be consistent with any ‘structural’ or physical views (young earth, old earth etc), have been taken by Christadelphian writers. For example, brethren have addressed: | It is noted that other approaches, which may be consistent with any ‘structural’ or physical views (young earth, old earth etc), have been taken by Christadelphian writers. For example, brethren have addressed: | ||

* “Literary, historical and theological analyses”<ref>{{SSnobelenr}}, ''The Genesis Creation – literary, historical and theological analyses,'' unpublished [?] (2013)< | * “Literary, historical and theological analyses”<ref>{{SSnobelenr}}, ''The Genesis Creation – literary, historical and theological analyses,'' unpublished [?] (2013)<blockquote>'''Note:''' if this is an academic work, SS's religion should not be relevant, and it might not be appropriate to list it here. — [[User:Bruce|Bruce]]</blockquote></ref> <ref> In this vein, I am aware of current discussion within our community concerning Gen 1 to 3 being ‘temple’ language or God manifestation language.</ref> | ||

* Textual – addressing elements of the text as instruction<ref> {{DLevinr}} ''The Creation Text – studies in Early Genesis,'' Christadelphian Tidings Publishing Co. (2011)</ref> | * Textual – addressing elements of the text as instruction<ref> {{DLevinr}} ''The Creation Text – studies in Early Genesis,'' Christadelphian Tidings Publishing Co. (2011)</ref> | ||

* Moral – '''''why''''' did God create?<ref>{{DWeatherr}}, op cit.</ref> | * Moral – '''''why''''' did God create?<ref>{{DWeatherr}}, op cit.</ref> | ||

Latest revision as of 14:39, 21 May 2023

← Index of

Early Genesis, A review of historical Christadelphian approaches

- by Bro Ken Chalmers, January, 2016

5. The language of early Genesis

5.1 Appearance and language of the day

It has generally been accepted as a principle in the past that the meaning of a Divine text should best be understood on the basis of how those to whom it first came and was read, would have received it. In addition, it has been recognized that the Bible is not written in scientific language.

“The Bible does not speak in the literal and strictly scientific language of the nineteenth century, but in the language of the day in which it was written (although it frequently anticipates the discoveries of modern science and uses words in harmony therewith). Any other style of writing would have failed to give information to those reading it.”[1]

Bro C. C. Walker writes similarly:

“The language of appearance is indeed used, just as we use it now, but there is no clash with truth. Moses’ testimony is not so ‘plain’ that it cannot be misinterpreted or misunderstood. He speaks of ‘the heaven and the earth’ as being in existence ‘in the beginning;’ and therefore it does not seem to be inadmissible to suppose that ‘the host of heaven’ was likewise then in existence. Moses’ testimony was given to Israel in what might be called the infancy of the world, when men did not know the extent of the earth, let alone that of the sun, moon, and stars. And, as we believe, it was given (by God through Moses), not so much to instruct Israel in cosmogony in detail, as to impress upon them the idea that the Most High God is the Possessor of Heaven and Earth (Gen. 14:22). And this against the claims of the gods of the nations, as was abundantly proved in Israel’s history.[2]

Similarly, others have written concerning the use of language:

“We must remember that these chapters were written to convey essential basic teaching to many generations of God’s people living in very different environments. For centuries, indeed for millennia, these early chapters of Genesis have borne witness to God’s creative power and purpose, written in language which could be easily understood by all men and in this respect in contrast to the constantly changing character of scientific views. This teaching, if it were to instruct each generation, must be written in language they could all understand. A creation story written in the language of Victorian science would have been unintelligible to all earlier generations and out of date for subsequent generations.”[3]

In more recent times, brethren have expressed themselves thus:

“We must begin by realising that Genesis was never intended to teach science. It was written in very simple language, to teach some profound truths to all mankind. Those simple words made sense to the Hebrews in the dawn of civilisation. The marvel is that they still make a very favourable impression on many scientists today.”[4]

The purpose of the Genesis record has previously been reflected by bro John Bilello as offering ‘scant’ account of the creative acts and process. Others have observed similarly:

“In the Bible, God reveals only selective facts which directly affect our eternal life. The Bible is not a science book, nor is it a history book. For example, the details in Genesis 1 are very selective and very brief, and they are not primarily scientific, although everything revealed is in harmony with the physical sciences.... God chose not to reveal to us how the heavens and earth were created, probably because very few people would be able to understand the physical process. To this very day, astrophysicists debate the mechanics of the primordial creation. . . ”[5]

“So why do we have the creation explained to us as it is? Based on a few simple observations, it appears to be untenable to suggest that the Genesis creation’s objective is to explain the How. The testimony of the simple creation language should lend weight to this observation. For example, ‘And God said, let there be lights: and there was light.’ (Genesis 1:3) But, how? What sort of light? Where did it shine? Did this include the rotation of the earth? Clearly, these are unimportant details for us in the wisdom of the almighty”.[6]

5.2 Early Genesis as Ancient Near Eastern literature?

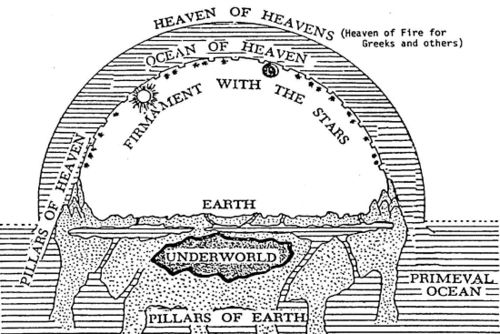

Recently, the language of Genesis as a response to Ancient Near Eastern (ANE) literature has received attention. These views have been recently addressed by bro Andrew Perry. The views are likely not new to some Christadelphians with writings by bro Wilfred Lambert being referenced a number of times in bro Perry’s treatise. His book also extensively references writings by evangelical theologians such as Walton[7] and Seely.[8] He includes the following figure which Seely and others have used which purports to describe how ancient Hebrews considered the firmament and earth elements:

Bro Perry’s conclusion is as follows:

“The genre of the Genesis creation account has changed through its being part of canonical Scripture. Scripture is intended for both Jews and Gentiles throughout the world. Although Genesis 1 has its roots in the ANE, the divine intention for the account is for it to be comprehensive for all of creation, wherever Scripture is taught and preached. It is therefore a mistake to both ignore its ANE roots and to discount its ‘all things’ application. The history of interpretation of Genesis 1 has ignored its roots and read the account in the light of planetary ‘science’ of the day, whether this has been Aristotelian or Copernican; it has also been read in the light of the sciences of Geology and Biology in recent times. Equally, and ironically, liberal scholars have misread Genesis just as an ANE cosmology. We need to avoid both mistakes. Instead, we should give the Genesis account its unique place within the Ancient Near East—a divinely revealed account to those chosen by God and ensure that we generalize the account to cover the creation of all things.”[9]

An element of this approach also addresses the word ‘firmament’ (Heb raqia) and notes that it depicts a ‘firm’ ceiling as it might appear to a primitive observer from earth.

5.3 Other approaches

It is noted that other approaches, which may be consistent with any ‘structural’ or physical views (young earth, old earth etc), have been taken by Christadelphian writers. For example, brethren have addressed:

- “Literary, historical and theological analyses”[10] [11]

- Textual – addressing elements of the text as instruction[12]

- Moral – why did God create?[13]

Some of these approaches are further described (e.g. ‘forming’ and ‘filling’) later in this paper. However, some of the above approaches draw attention to the literary construction of the record, the importance and number of times that particular phrases or words etc occur, and the key themes of ‘light and darkness’, ‘fruitfulness’ etc, which clearly have relevance to those who are the ‘new creation’.

- ↑ Clement, D, The Creative Order – Mosaic and Geological, The Christadelphian, v21, p176 (1884)

- ↑ Walker, C C, The Christadelphian, v50 p348 (1913)

- ↑ Bedwell, W. Letters to the Editor, ‘The Origin of Man’, The Christadelphian, v102, p510 (1965)

- ↑ Hayward, A, God’s Truth, p 212, Marshall Morgan and Scott (1973)

- ↑ Styles, E, The Allegory of Genesis 1, Tidings magazine, (Nov 2009) accessed on 12/11/2015, at tidings.org.

- ↑ Weatherall, D, Create in Me – the power of the Genesis Creation, p 13, self published (2010)

- ↑ E.g. Walton, John, The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate, InterVarsity Press, 2009

- ↑ Seely, P H, The Firmament and the Water Above, Part 1: The meaning of raqia in Gen 1:6-8, WTJ, v53 (1991) – see updated link here.

- ↑ Perry, A, Historical Creationism, p119, Willow Publications (2013)

- ↑ Snobelen, S, The Genesis Creation – literary, historical and theological analyses, unpublished [?] (2013)

Note: if this is an academic work, SS's religion should not be relevant, and it might not be appropriate to list it here. — Bruce

- ↑ In this vein, I am aware of current discussion within our community concerning Gen 1 to 3 being ‘temple’ language or God manifestation language.

- ↑ Levin, D The Creation Text – studies in Early Genesis, Christadelphian Tidings Publishing Co. (2011)

- ↑ Weatherall, D, op cit.